An interesting piece of news appeared recently.

A German car dealer went out of his way to buy 22 Volkswagen ID.6 cars from China and import them to Germany.

Wait, a German nation imported a German electric car from China into Germany?

Well, this particular ID.6 imported from China is selling in Germany at a starting point of ¥259,888 or US$36,500 / €33,700. In addition to that, the ID.6 is available EXCLUSIVELY in China.

As a comparison, “in Germany, the smaller wheelbase ID.4 starts at €40,335 or $43,600“.

But wait, this is not the end of this story. Volkswagen is now suing the car dealer:

VW issued a temporary injunction against Brudny. In a subsequent judgment, a court ruled that the vehicles should be seized, and now VW wants them to be destroyed.

So what is actually happening here? And why it does matter to all investors everywhere?

Very Different Prices

The core of the idea, beyond the unavailability of ID.6 on the German market is the price difference, with ID.6 cheaper than smaller models made and sold in Germany.

This is not the only outrageous price difference between Germany and China for the same car models:

“VW sold the ID.3 for as low as €16,000 or US$17,300, compared to its starting price in Germany of €40,000 or US$43,300.

Similarly, the ID.7 Vizzion starts at ¥237,700 in China, equivalent to $33,400 or €30,800, while it costs nearly twice as much (+88%) in Germany at €56,995 or US$61,600.”

So both ID.3 and ID.7 are selling roughly for double the price in Germany compared to China.

VW argues that this is because of different safety standards, but this is likely bogus for a few reasons:

“After a few modifications and a software update, the country’s transport authority was prepared to sign off on the vehicles, and he was legally allowed to sell them.”

So the German government itself says the cars were safe to sell.

Volkswagen said models produced in China are different from those for sale in Europe and lack certain legal requirements, such as an automatic emergency call system.

How expensive or complex would such an emergency call system be to add to the cars?

And why would VW actively pursue the cars to be destroyed? Not just sent back to China or modified, but destroyed.

Evidently, more is at play here than a mere concern about safety standards.

Different Industrial Competitivity

The issue here is made of a few components:

VW does not want German consumers to realize that Chinese consumers are paying half price for the same models, minus a few minor changes.

VW is likely utterly unable to produce the cars at this price out of China.

VW would jeopardize its cozy relations with the German government, as well as with the local unions if it admitted that what made more sense businesswise would be to move production to China.

I fully expect the unfortunate car dealer to lose the case. The initial acceptance by the regulatory authorities of his import was a blunder that will be corrected.

Because it highlights a few uncomfortable truths:

Even before running out of German gas, the German heavy industry was not competitive anymore.

Despite heavy subsidies and political circus, most green tech is MUCH cheaper when made in China.

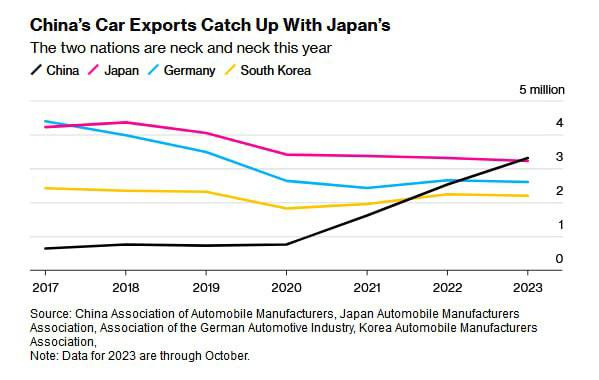

In 2023, China has become the world’s largest auto exporter, outclassing both Germany and Japan at their own game.

Chinese factories are more advanced and more performant than any other in the world.

Don’t take my word for it, listen to the head of the Toyota EV division, in the Financial Times “For the first time, I came face to face with the competitiveness of Chinese components. Laying eyes on equipment that I had never seen in Japan and their state-of-the-art manufacturing, I was struck by a sense of crisis”

A New Industrial Power Has emerged

For a long time, China’s industry grew out of cheap labor and lax environmental and work regulations.

But in the last 10 years, Chinese wages have risen dramatically, and so has the cost of living.

Doom sayers predicted that factories would move out of China toward Vietnam, Indonesia, or India, leaving China stuck in the famous “Middle Income Trap”.

The demographic decline would add to these woes, leaving too few workers to create any economic growth.

Instead, Chinese companies are now out-competing German and Japanese automakers, which were previously thought to be the top of the industry, dominating the less efficient American, French, or Italian automakers.

This is not unique to cars, but a trend in all advanced, high-added value industries.

A year ago, talks of China's semiconductor industry being “destroyed overnight” by US sanctions were the mainstream narrative.

In November 2023 “China's semiconductor equipment manufacturing sector saw a 33.9 percent year-on-year increase“. While still dependent on Western-made components, this dependence is fading quickly.

In January 2024 “Western nations need a plan for when China floods the chip market“. (FT).

War on the Rock elaborates further:

“Over the next 3 to 5 years, China is expected to add ‘nearly as much new 50-180 nanometer wafer capacity as the rest of the world’ as well as construct 26 fabrication plants through 2026 that use 200-millimeter and 300-millimeter wafers — 10 more plants than in the Americas.“

“half to two-thirds of the silicon used in the new Huawei phones was produced domestically in China. Previously, this amount was only one third.“

In February 2024 “China on the cusp of next-generation chip production despite US curbs“. (FT)

Some will argue that for now, the Chinese chip-making process is less efficient than decades-long optimized processes from TSMC, and this is true. But with 2B+ people in reach (China, Russia, Belarus, Iran, etc.), how long will this take to get the scale and experience required?

A 4th Generation Industrial Powerhouse

How did this happen?

In only one word? Automation.

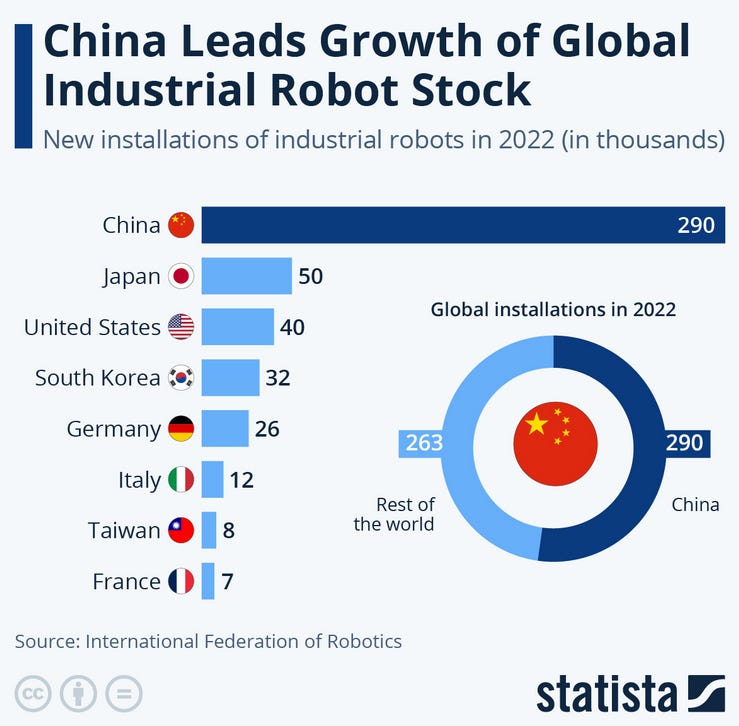

China accounted for half of the industrial robots installed in the world in 2022. The Chinese robot demand was up 8% year-to-year.

This gives Germany slightly more robots per thousand inhabitants (0.31) than China (0.2). But more on that later.

So much for re-industrialization…

The Power Of Scale

The key part here is not so much the number of robots, in absolute terms or per capita. But the presence of a massive ecosystem and a dense supply chain.

When building actual things, instead of just software and designs, scale matters.

A larger scale means more engineers learning on the job.

More amortization of heavy infrastructure like cranes, deep-sea harbors, railroads, etc.

Larger cohorts of university students training in related fields (metallurgy, robotics, automation, etc.) lead to a denser professional network and more niche roles.

More niche roles allow for more specialization and innovation. It also allows for more optimization of processes, with something making sense to specialize only if it serves a market made of billions of people, but not tens of millions.

A larger industry spreads the same R&D effort over more units produced.

This in turn allows for innovative design to be cheaper, which feeds more scale, which feeds more R&D, which makes innovation cheaper, and so on…

The Answer?

Probably NOT that:

There is very little that can be done to compete with an efficient super large country in industrial policy. There is a reason why by 1935 (even before the war) the USA industrially dominated ALL the European powers, even if they had a headstart.

Simply put, a larger market creates more scale which creates more competition through multiple mechanisms (more skilled workers, better infrastructure amortization, more margins, more R&D, cheaper products, etc.).

The alternative is peaceful collaboration and specialization. Europe could not compete with American chips, but it could outperform in French fine wine, niche German tech, etc.

But of course, this implies admitting that the largest country will somewhat “rule” you, something the US will not accept from China until after a revolution in domestic political culture…

Another option is BECOMING as big as the competitor. But this means full integration in a fair and efficient manner with other countries. Something that the US and even the EU have so far failed to achieve.

Maybe under pressure, it will happen, but there is not even the beginning of a sign of it, so probably not for another decade. Or two. Or three.

Conclusion

I intend to start at some point an in-depth analysis of China’s economic and industrial prospects for the next 5-20 years. This article could be viewed as an introduction to the topic.

Judging from electricity consumption, car exports, progress on chips, etc. I am utterly convinced that China is not going anywhere.

Short of a global conflict.

And actually, not even in that case, if the example of the USA in the 1930s is used as a template.

It's refreshing to read a different take than the negative one which is omnipresent in the western mainstream media. What you have written is sensible and supported by evidence rather than a product of shallow, often subtly racist, pontificating. I'm looking forward to your next articles.