“Gold is for the mistress

silver for the maid

Copper for the craftsman cunning at his trade

"Good!" said the Baron, sitting in his hall,

"But Iron -- Cold Iron -- is master of them all.”

― Rudyard Kipling

The Allure Of Commodities

When looking at cyclical investing, it is hard to not get automatically drawn to commodities.

The tales of quick fortune and massive disasters are the thing of epics and legends.

And there is also the adventurous vibe of it, a remote location in an undeveloped country, and the ore motherload that can make the daring and lucky miners and mining company (or its shareholders) rich.

There are the usual suspects that draw the attention of the crowd:

Gold, silver, diamond, platinum, and other shiny things.

Then there are the expert and technical ones, whose appeal is secret knowledge missed by the market at large, ideally with some looming shortages due to upcoming explosive demand growth:

Lithium, copper, rare earth, tungsten, titanium, and other exotic materials for a new space age.

If this interests you, I have already covered some of that in a previous report:

Then there is the stuff that powers the world and always seems at the edge of running out as we are always collectively eager for more power, more air conditioning, more cars, MORE!:

Oil, gas, coal, uranium, etc.

And then there is the key commodity-like manufactured products and machines, the raw material needed to keep the world functioning:

Polysilicon, semiconductors, steel, ships, etc.

The Boring Stuff

This leaves some commodities in the “boring” category. The stuff that is displaying some characteristics that are too dull to make a good story of.

Not rare enough to be worth a fortune or be hard to find.

No new technology to justify a bull case.

No true scarcity nor chronic deficit.

And most industrial commodities fall into this category:

Aluminum, sand for concrete, and more than anything, IRON.

Iron is that element that humankind has built its civilization on since at least the Hittite Empire, at the end of the deep Antiquity of the Bronze Age.

From swords, horseshoes & plows to the steam engine & the Eiffel Tower, iron is the literal backbone of every technological leap made by humankind.

Today, it is used not so much in the form of pure iron but also in the shape of steel (most steels are 95-99% iron).

And we need a lot of it. Actually almost an unimaginable amount of it.

In 2023, we consumed 1.6 billion tons of iron, or 1.6 TRILLION kilos. This is 195kg per person in the world.

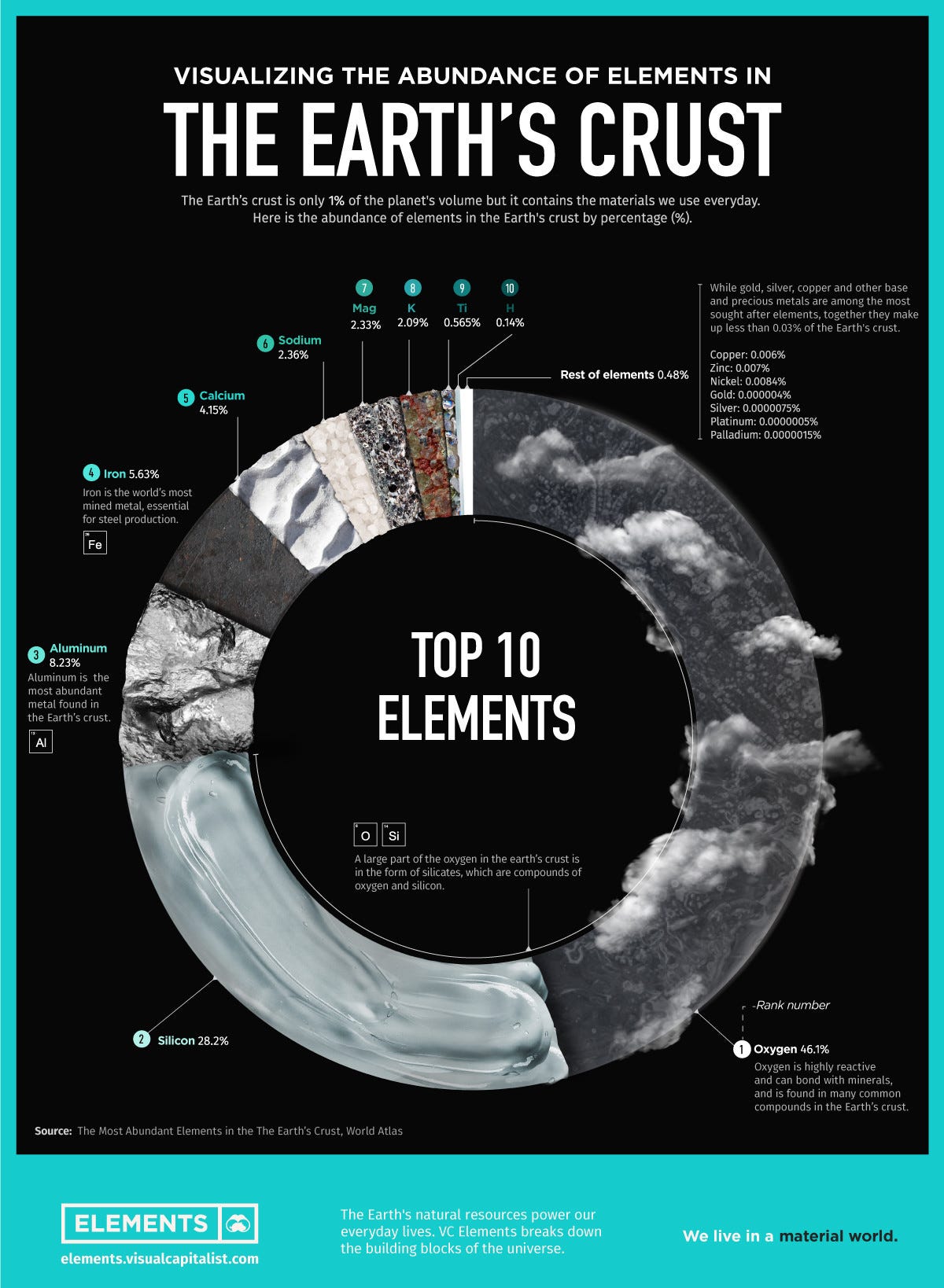

So we are lucky this is the 4th most common element on Earth's crust, just below aluminum and above calcium or sodium.

It is a somewhat invisible consumption, embedded in our cars, trucks, ships, concrete, pipelines, etc.

Who Does What?

Over time, the leading producer of steel, the most strategically important form of iron consumption, keeps changing along with the mantle of geopolitical influence.

The Swedish empire was a powerhouse in large part thanks to its massive artillery park, and so was Great Britain and later the US thanks to their large steel-made warships. Each peaked around 50-60% of the world’s steel production, plateaued for 50 years, and then declined.

Unsurprisingly, China is the new rising power of the world, and its steel production is moving accordingly.

Note that the graph is not fully up to date, the current China share is 57%.

A chart in relative percentages tells us the relative power story, but not the raw consumption.

China's rise in the percentage of steel production is accompanying a parallel rise in global steel (and iron demand).

Can you spot the rise of the China era?

The production of steel over the last few decades is larger than the CUMULATED production since the birth of civilization!

Where does it go?

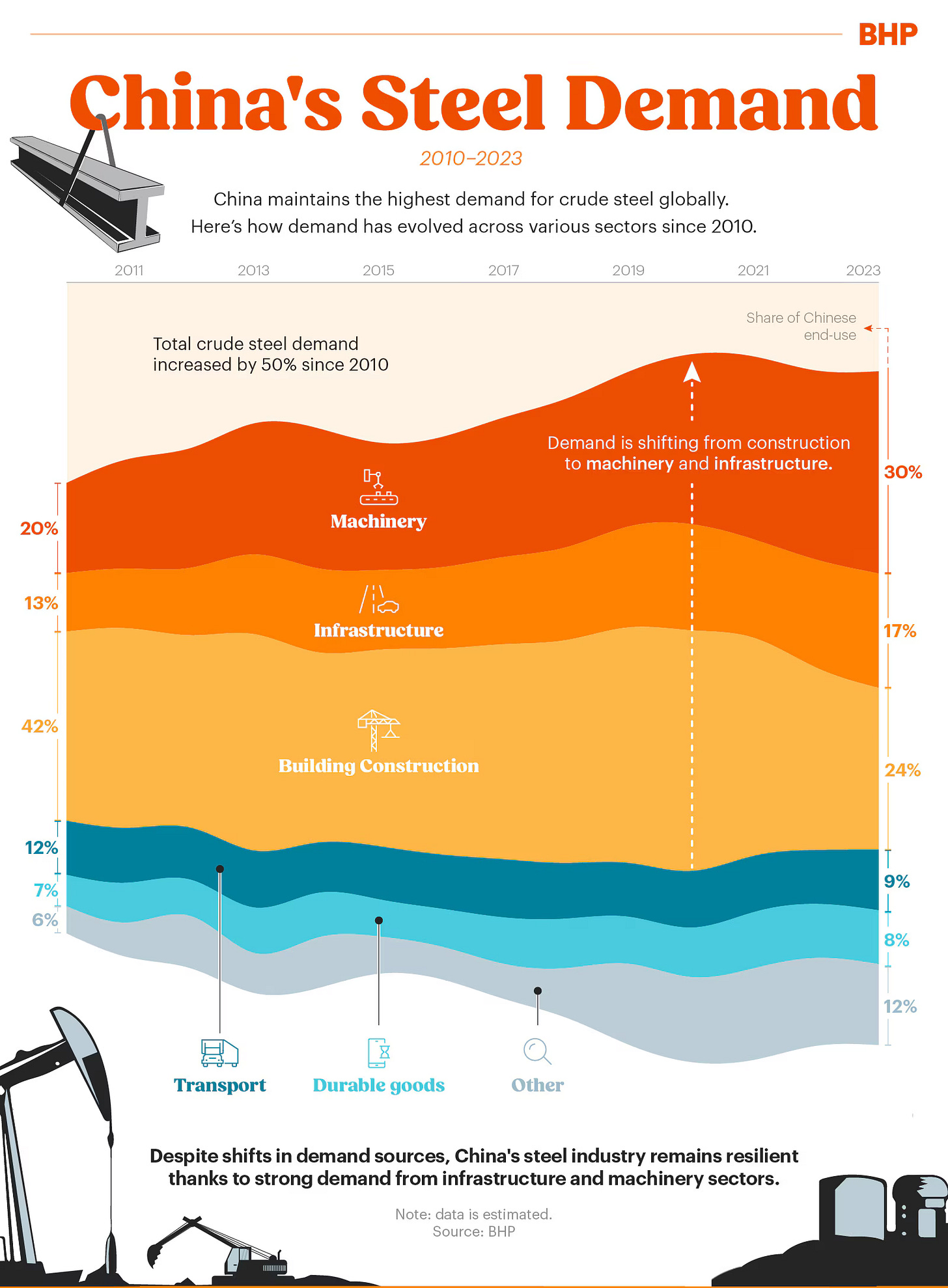

It used to be in construction and infrastructure, which is no surprise when entire megapolises emerged from nowhere and the country is covered with tens of thousands of bridges and hundreds of thousands of kilometers of railroad.

But this is less and less true, with most of the production now going into machinery, from industrial robots to tractors, excavators, tools, ships, and even drones (more than half of the world's ships are made in China).

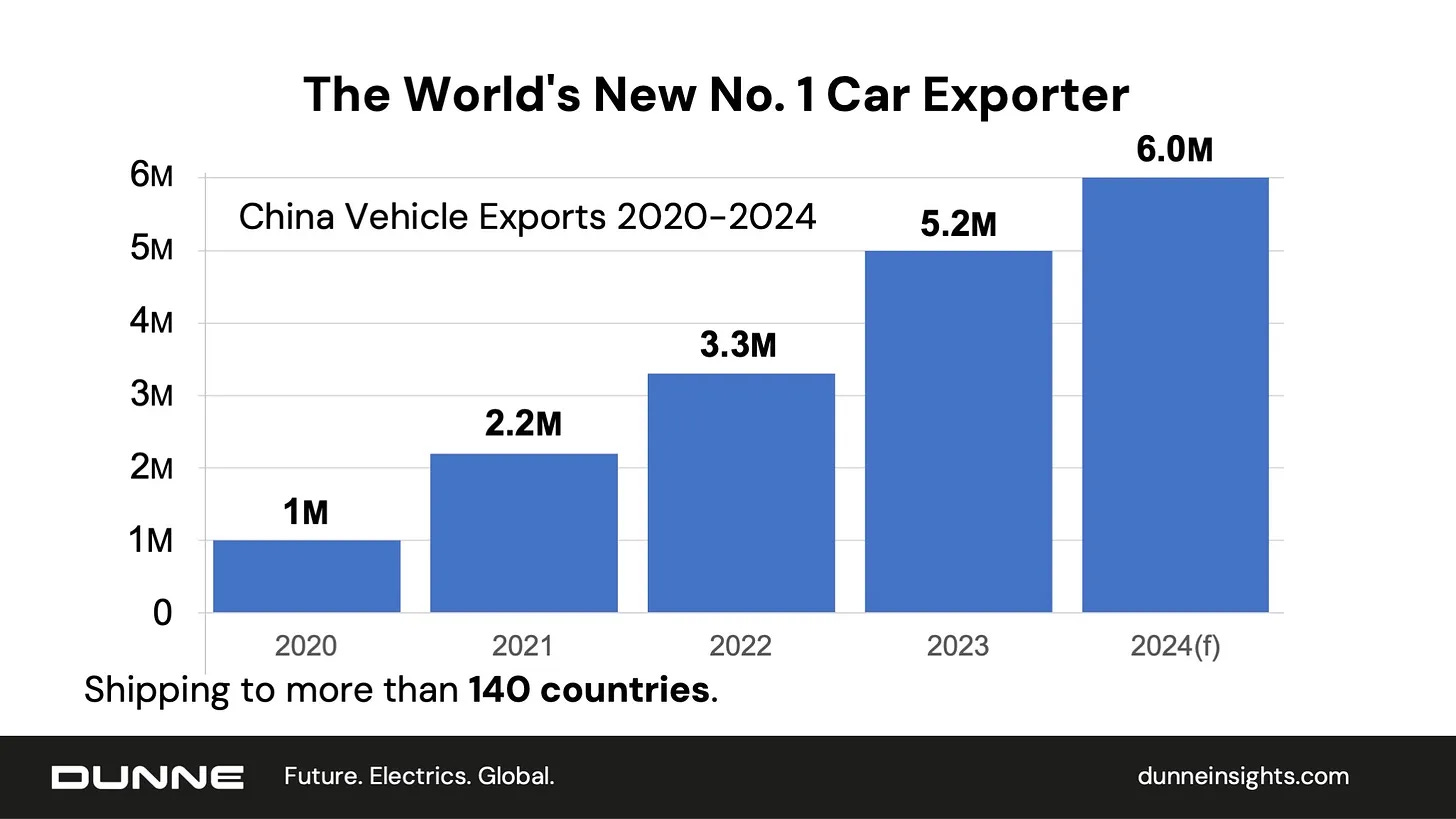

When it comes to future demand, cars & trucks (lump in transport above) will certainly be a growth story, especially as China’s automotive exports look like this:

6x in 4 years!

They’re not selling solely EVs: they’ve taken share in multiple segments and powertrains.

You can read more on the excellent Dunne Substack for more info about how China is quickly storming the world of automotive production:

We will come back to that topic later.

Where Does It Come From?

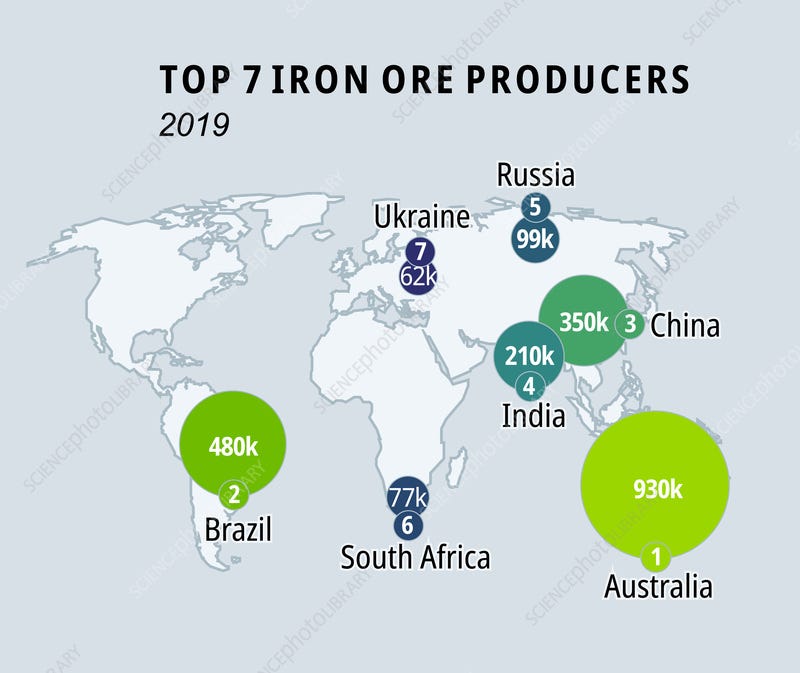

While abundant, the world’s iron ore reserves are unequally spread.

Explaining its original lead, tiny Sweden is today among the Top 12 larger iron reserves on Earth.

It is also abundant in the usual suspects of Russia & Ukraine (mostly in the Donbass for that matter), and China.

The largest reserve is in Australia (50 billion tons), which made the core business of mining giant BHP and Rio Tinto, now diversified global miner, even if the core of their business is still iron.

And make no mistake, these are 2 solid companies and I even owned Rio Tinto shares for a while.

Unfortunately, Australian miners are not necessarily cheap, reducing the attractiveness of their stock, even if the business is solid.

Another country, with the 2nd largest reserve, is Brazil, with 34 billion tons of iron ore. And as my regular readers certainly know, it is a country whose stocks are dirt cheap currently.

Brazil is also very much a global player in this field, ranking second in total production. But as you can notice below, it produces barely twice more as India, despite ore reserves 6x larger.

So there could be plenty of room for growth.

And at the core of Brazilian iron production is one company: the iron ore giant Vale